The Monty Hall Problem - Part 1

A Counterintuitive Probability Brainteaser

The Monty Hall Problem is a famous probability brainteaser based on a game show scenario. It is named after Monty Hall, the original host of the television game show “Let’s Make a Deal.” The problem is known for its counterintuitive solution, which often surprises people - and still sparks debate among statisticians and enthusiasts alike.

The problem was first posed by Steve Selvin in a letter to the journal “The American Statistician” in 1975. It gained widespread attention after being featured in Marilyn vos Savant’s “Ask Marilyn” column in Parade magazine in 1990.

Marilyn’s response sparked a significant public debate, as many readers found disagreed with her solution and explanation. The Monty Hall Problem has since become a classic example in probability theory and is often used to illustrate the importance of considering all available information when making decisions, and who exactly is privy to that information.

We’ll explore the problem, its solution, and the reasoning behind it.

The basic problem statement

The original problem is as follows:

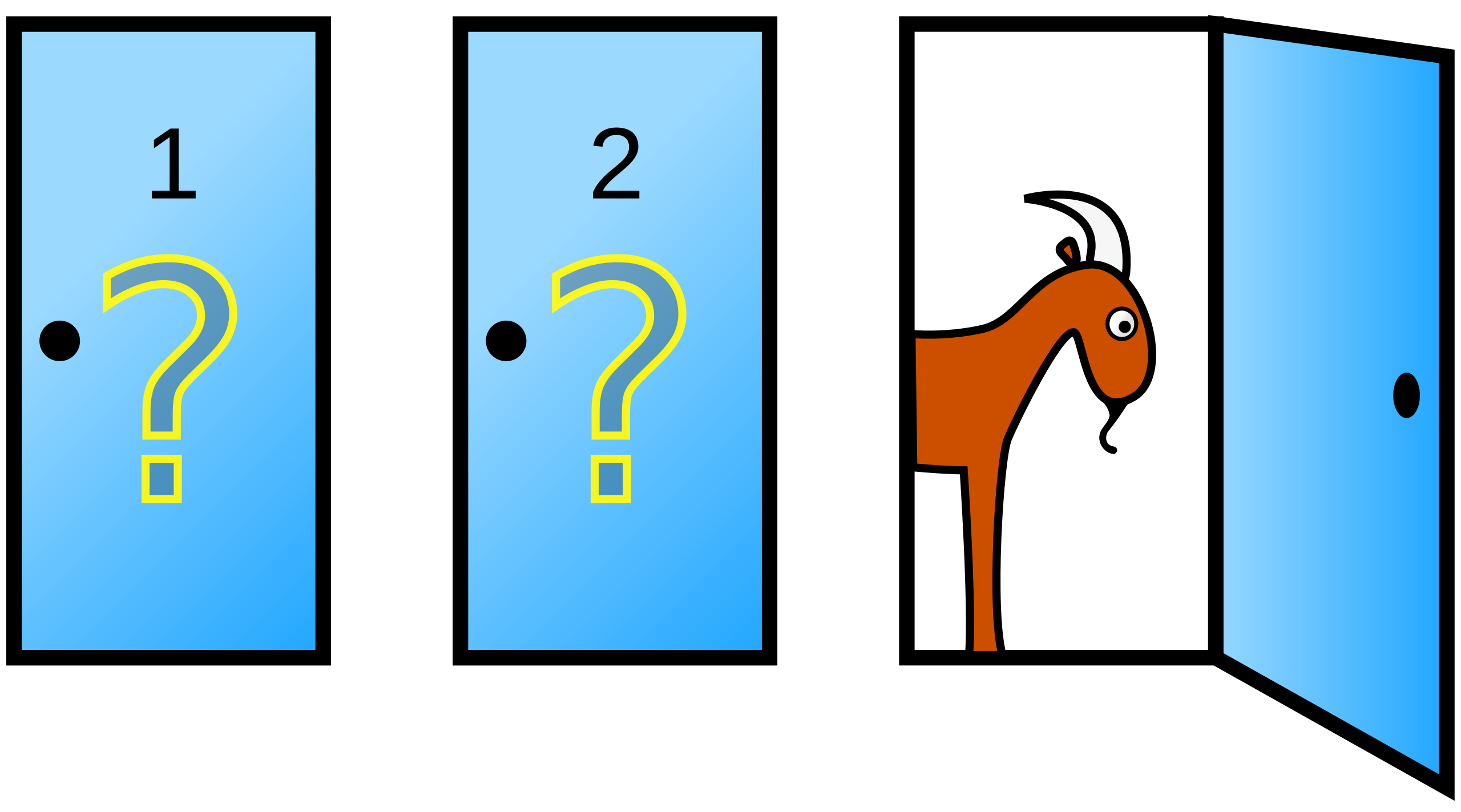

- You are a contestant on a game show.

- There are three doors: behind one door is a car (the prize you want), and behind the other two doors are goats (which you don’t want).

- You pick one door (say, Door 1).

- The host, who knows what’s behind all the doors, opens another door (say, Door 3) that has a goat behind it.

- The host then gives you the option to switch your choice to the remaining unopened door (Door 2) or stick with your original choice (Door 1).

What should you do to maximize your chances of winning the car?

The immediate intuition might suggest that after Monty offers us the switch, we now only have two doors to choose from, with each being equally likely, i.e. the odds being 50/50. So it does not matter whether we switch or stay. However, this is not the case.

Vos Savant’s solutions was that you should always switch doors.

Why? By switching, you have a 2/3 chance of winning the car, while if you stick with your original choice, you only have a 1/3 chance. However, this solution is dependent on the exact problem statement given. If the problem statement is changed, in particular the host’s behavior, the solution may also change.

The disagreements and debates around the Monty Hall Problem often stem from misunderstandings of the problem’s conditions and the role of the host’s actions. Many people assume that the host’s choice to open a door is random, but in reality, the host always opens a door with a goat behind it, which provides additional information that affects the probabilities. In technical terms, the host’s actions are not independent from the contestant’s choice, and this dependency is crucial to understanding the correct solution.

The original Ask Marilyn column, vos Savant’s response, and subsequent reader correspondence be found here.

It’s all about what information is known

The fundamentals of stochastic problems are directly related to what information is known and by whom.

A common assumption in stochastic processes is that different events are Independent and Identically Distributed (i.i.d). This means that one event does not affect any subsequent events, and they are drawn from the same probability distribution. If a subsequent event is dependent on the outcome of a previous event, we’d have to look at conditional probabilites given the outcome of the first event.

In the beginning, we have three doors, and the probability of the car being behind any door is 1/3. When you pick a door, you have a 1/3 chance of having picked the car and a 2/3 chance of having picked a goat. We do not know where the car is, and do not have any other information at this time to help us make a better choice. The probabilities are uniformly distributed between all options.

However, after we make our initial choice, the host’s action is not random - it’s deterministic and dependent our chosen door and where the car is (which he knows).

Therein lies the key to understanding the problem

The host knows where the car is and once we choose a door, he will always open a door that has a goat behind it. This biased action provides us with new information that changes the probabilities. We can reinforce this understanding by considering the following:

- The host will never open the door you initially picked.

- The host knows where the car is and will always open a door with a goat behind it.

Out of the two doors we did not choose, the host’s choice between those two doors provides valuable information to our problem which is not random, and thus allows us to update our probabilities for the remaining two unopened doors.

However, had the host opened a door at random, even possibly the one we initially picked, the probabilities would remain 50/50 between the two remaining doors, as no new information would have been provided that allows us to updated our probabilities from the initial uniform probabilities. In other words, the host’s choices would be Independent and Identically Distributed as our choice of door to open.

The solution

So, here is the full solution.

We have gone over the probabilities at the initial choice of door by the contestant, the one chosen has probability \(p=1/3\) of having the car, the other two doors have a combined probability of \(1-p=2/3\) of having the car. The probabilities add up to 1 since there is only one car and one door must be opened - i.e. something will happen, either a car is revealed or not.

Although there is 2/3 probability of the car being behind either of the other two doors, we don’t know which one out of those two to pick. We need more information to make a better choice.

However, the host’s knowledge and actions will help us with this problem. Since the host will only choose a door out of the two unchosen doors, and will never open the door with the car - should it be behind either of them - the other door he did not choose becomes more valuable to us, since the full 2/3 probability of the car being behind either of the two unchosen doors now tranfers fully to the door not chosen by the host. We now don’t have to choose between the other two doors, the host has eliminated one for us free of charge. This is called variable change - i.e the actions by the host changes the variables of our problem.

There is a famous classroom scene in the movie “21” from 2008 where this is explained quite well (see below). There is also a great numberphile video explaining the problem and solution in detail.

Here is the scene from 21:

Here is the numberphile video:

The scene from 21 is also of interest from the other topic discussed, namely Newton’s method - or Newton-Raphson method - for finding roots of functions and the possible issues with that method. This is a topic for another time though.

Different host behavior

It is important to note that the solution to the Monty Hall Problem is dependent on the host’s behavior. If the host’s actions were different, the probabilities and optimal strategy could change. For example, if the host were to open a door at random, without knowledge of what is behind the doors, the probabilities would indeed be 50/50 between the two remaining doors after one is opened, and switching or staying would not matter. In other words, such behaviour by the host would not provide any additional information to the contestant.

We can look at various different host behaviors and see how they affect the solution:

Host always opens a door with a goat (standard Monty Hall Problem): The optimal strategy is to always switch, giving a 2/3 chance of winning the car.

Host opens a door at random: It does not matter if you stick with your first choice or change to the other remaining door, as the probabilities are 50/50 between the two remaining doors.

Host only opens a door if the contestant initially picked the car: In this case, the optimal strategy is to always stick with the original choice, as switching would lead to a guaranteed loss.

Host opens a door only if the contestant initially picked a goat: Here, the optimal strategy is to always switch, as switching would lead to a guaranteed win.

These variations illustrate how the host’s behavior can significantly impact the probabilities and optimal strategies in the Monty Hall Problem.

How do we know that Monty is biased?

This is an interesting question to ask. Our solution is based on our knowledge of how Monty behaves in the way we have assumed. However, say we were seeing this game for the first time, do we know that Monty is biased?

Well, the simple answer would be no. However, because Monty opens a door, one might think that he does not do that at random and would never do so to reveal the car. If that is a natural assumption to make, then what about Monty opening the door that we chose if it does not hide the car? That would reset the game and increase the probability of us finding the car from 1/3 to 1/2 in the new selection - a 50% increase in probability! It would not make sense for Monty to do that. The final option is for Monty to behave as we assume - i.e. he always opes a door with a goat and never our chosen door.

If we just initially assume Monty behaves randomly, we’d see from repeated trials, that Monty’s choices are not random and are most likely biased in a logical way for him.

Reinforcement through simulation

To further reinforce the understanding of the Monty Hall Problem, we can simulate the game multiple times to see how often switching versus staying leads to winning the car. Below is a simple Python simulation that demonstrates this. The contestant and host choices are randomly (pseud-randomly) generated to mimic the game scenario. The simulation is run for a large number of trials to get statistically significant results, providing a point estimate of the probability of choosing the right door \(p\) vs. switching \(1-p\).

This code is essentially simulating a Bernoulli process where each trial results in either a win or a loss based on the chosen strategy (switching or staying). By running the simulation multiple times, we can estimate the sample probabilities of winning for each strategy, taking advantage of the law of large numbers for the sample probabilities converging towards the true probabilities.

Run the following code cell by clicking “RUN CODE” in the upper right corner. Adjust the code as you please to experiment with different numbers of trials or strategies.

/Röx